A Peasant Like Me

My name is Adugnaw Worku and I was born and brought up in northwest Ethiopia. My parents were peasant farmers like everyone else in the area and I was destined to continue the family tradition as a country farmer. From age seven to twelve, I was a shepherd and my assignment was taking care of goats, sheep, and cattle. At age twelve, I handed over the shepherding assignment to my younger brother and moved on to the family farm. My father taught me what his father had taught him about farming. He taught me how to harness the oxen, how to plow in a straight line, how to sow the seeds, how to weed, and how to harvest. I worked side by side with my father and I was fully trained by age fifteen. Every year, we planted and harvested various crops we needed to live on. We had to buy salt, shirts and pants and some farm equipment in the open market and cash crops like oil seeds, cotton, and spice made it possible for us to do so.

My name is Adugnaw Worku and I was born and brought up in northwest Ethiopia. My parents were peasant farmers like everyone else in the area and I was destined to continue the family tradition as a country farmer. From age seven to twelve, I was a shepherd and my assignment was taking care of goats, sheep, and cattle. At age twelve, I handed over the shepherding assignment to my younger brother and moved on to the family farm. My father taught me what his father had taught him about farming. He taught me how to harness the oxen, how to plow in a straight line, how to sow the seeds, how to weed, and how to harvest. I worked side by side with my father and I was fully trained by age fifteen. Every year, we planted and harvested various crops we needed to live on. We had to buy salt, shirts and pants and some farm equipment in the open market and cash crops like oil seeds, cotton, and spice made it possible for us to do so.

Work on the family farm was backbreaking and the farm equipment we used was primitive and ineffective. We depended completely on seasonal rhythms and weather patterns and hoped and prayed for rain constantly. There were no reservoirs to capture rainfall, and we did not use river dams for irrigation. Consequently, we had only one harvest a year and that did not give us adequate reserves for emergencies. One bad season with little or no rain often put us in precarious situations almost immediately.

In short, my recollections of life on the family farm are mixed at best. There were happy times to be sure. As long as we had adequate rain and a good harvest, we were able to enjoy weddings, holidays, and the many social and religious festivities with family and friends. But we lived a year at a time and almost always on the edge. We depended on God and on our own ingenuity to survive. I have absolutely no recollection that the government did anything for us by way of educating us to become better farmers, or helping us develop better farm tools. There was no health care of any kind and infectious diseases wreaked havoc in our lives. A lot of children died in those days. My poor parents lost seven children. The government did absolutely nothing to help us. What I remember is the additional burdens the government imposed on us every year. And what a burden that was! The tax collectors showed up right after harvest every year and demanded an arm and a leg. They were harsh and very callous.

In short, my recollections of life on the family farm are mixed at best. There were happy times to be sure. As long as we had adequate rain and a good harvest, we were able to enjoy weddings, holidays, and the many social and religious festivities with family and friends. But we lived a year at a time and almost always on the edge. We depended on God and on our own ingenuity to survive. I have absolutely no recollection that the government did anything for us by way of educating us to become better farmers, or helping us develop better farm tools. There was no health care of any kind and infectious diseases wreaked havoc in our lives. A lot of children died in those days. My poor parents lost seven children. The government did absolutely nothing to help us. What I remember is the additional burdens the government imposed on us every year. And what a burden that was! The tax collectors showed up right after harvest every year and demanded an arm and a leg. They were harsh and very callous.

My parents were very intelligent and proud Ethiopians. My father fought against the Italian occupiers for five years and he voluntarily served as a community leader during most of his adult life. Unfortunately, my parents were illiterate. They had no opportunity to learn to read and write, or even sign their names. Religious education existed in Ethiopia for hundreds of years but it was limited to those chosen to serve the church and the government. As a child, I was very curious and enjoyed learning new things. I recognized the value of education instinctively and begged my father to allow me to attend the local priest school. Some of my childhood friends were attending priest schools and they were able to read, sing, and serve in the local churches. But my father told me in no uncertain terms that being a farmer was better than being a priest. His best wishes and desires for me were to be a good and successful farmer, get married, raise a family, and continue the family tradition of farming. I was not satisfied or pleased with my father's vision for my life and I took matters into my own hands when I was about nine years old. I left home without my father's permission and enrolled myself in a priest school far from home, so I thought. I was enjoying school and I was learning a lot. But one day, my father showed up from nowhere and told me to pick up my belongings and go home. I returned home broken-hearted and very unhappy. Fortunately, that was not the end of the story because better educational opportunities came later and unexpectedly.

When I was fifteen years old, an unexpected event drastically changed the course of life. I had a freak accident which left me blind in the left eye. My lens was destroyed and my cornea was scratched. In addition, I developed a traumatic cataract on that same eye with a white patch covering the middle of it. Both the loss of vision and the disfigurement were hard to take for me personally and for the family as a whole. The best medicine men and women in my village and in the surrounding area tried to help me. But the accident was too severe to respond to traditional herbal medication. In desperation, my family decided to send me to a modern hospital for treatment. I walked with a group of merchants for two days to reach a city called Debretabor. This was the first time I was away from home and the farthest I had ever travelled. I was full of anxiety, expectation, and hope. I had not been to a big city before and Debretabor appeared to me to be a big city. Some of my mother's relatives lived in Debretabor and finding out where they lived was my first a challenge. In the countryside, everybody knew where everybody else lived but it was not so in the big city.

The hospital at Debretabor was a Seventh-day Adventist hospital and the physician at the time was a missionary doctor from Norway by the name of Dr. Christian Hogganvik. Dr. Hogganvik looked at my eye and shook his head. Then he informed me through a translator that he was not an eye doctor and that I had to go either to Asmera or Addis Ababa. Once again, I was very disappointed. But something wonderful and profoundly life-changing happened to me while I was in Debretabor. I observed boys and girls going to school every day. And they were able to read and write. Here I was more than twice their age at fifteen years of age unable to even sign my name. Once more, I took matters into my own hands and did not seek my father's permission. I decided to go to school by whatever means I could possibly find. I had only two Ethiopian Birr in my pocket and I had nothing more than the clothes on my back. But my desire for education was intense and I was prepared to do anything. What I did next amazes even me in hind sight.

I literally went from door to door and asked people to give me food and shelter in exchange for work after school. In those days, school was only in the morning and the whole afternoon was available to work on the farm or in the garden. When I asked for food and shelter in exchange for work after school, some people laughed at me. Others admired my determination and felt sorry for me for attempting the impossible. But with luck, determination, and providential help, I became a proud first grade student at the age of fifteen and half, and I never looked back. I found school much easier than farm work and thoroughly enjoyed the enlightenment and the pleasure it brought to my life. By the time I reached grade eight, I had lived with five different families who treated me with love, kindness, and generosity. In my spare time, I cut grass and gathered and carried fire

wood from the forest and sold them to earn money for clothes and school supplies. I am eternally grateful to those generous Ethiopian families that came to my rescue during those critical early years of my education and for treating me as if I was their son.

When I was in grade eight, an American missionary family from the United States came to Debretabor and one of the family members by the name of Carolyn Stuyvesant became my teacher. I got to know this wonderful missionary family well and eventually asked them if they could help one of my brothers to come to school. To my pleasant surprise, they agreed. In exchange, I worked for them. A year later, this wonderful missionary family volunteered to help my other brother and my sister who were still at home. Today, all four of us are college educated.

I owe Dr. Harvey Heidinger, his wife, Elizabeth, and her sister Carolyn Stuyvesant a debt of gratitude more than words can ever express. These people of God changed our lives dramatically. Who would have thought that four peasant children from the same family would attend school and eventually graduate with university degrees? I started school very late, but I got it done eventually. I graduated from grade eight at age twenty two and from high school at twenty six. Then, I got an opportunity to go to Australia for my college education and graduated there at age thirty. Today, I hold three graduate degrees and an honorary doctorate. What a difference education makes! I thank God and people of good will for giving me the best gift in life, which is the gift of education.

My regret in life has been that I have not returned home to Ethiopia to help my country and my

people with the education and experience I have gained. I have been around the world; I have written two books and numerous articles, and I have produced CDs and DVDs of music and poetry. I have been fortunate and enormously blessed. But the boys and girls I grew up with in my village and in the surrounding villages have not been so fortunate. They never got the opportunity to realize their potential. I find that profoundly sad. I think of them often and wish that they had the same opportunity I have had. I can only imagine what they would have become if they were educated. To this day, their potential remains shrouded in a dense fog of ignorance, superstition, and grinding poverty. Life is very difficult for them and they struggle daily to make ends meet. To think that I can make more money in a few days than they can in a whole year is simply astounding. Education made that possible for me.

I dream day and night about Ethiopia and my people and I talk, write, and sing about them. Most of my professional and recreational writing and music has to do with homeland. As mentioned earlier, I have written two books and numerous articles. I have produced cassette tapes, CDs and DVDs and they are all about home sweet home. I play three Ethiopian traditional musical instruments, namely, washint, kerrar, and masinko and this has enabled me to put some of my poems to music and express how I feel deep inside. I am successful personally and professionally and I have reached the peak of my profession. But I never forget my roots and my humble background. The depth from which I have come and the heights to which I have climbed would not have been possible without God's blessings, people's generosities, and my own relentless quest for education and adventure. I am and will remain exceedingly grateful for all the blessings I have enjoyed in life. My philosophy in life is to reach out and help people in the same way that others reached out to me when I needed their help. With God's help, I will continue helping others in need as I have been helped when in need.

I dream day and night about Ethiopia and my people and I talk, write, and sing about them. Most of my professional and recreational writing and music has to do with homeland. As mentioned earlier, I have written two books and numerous articles. I have produced cassette tapes, CDs and DVDs and they are all about home sweet home. I play three Ethiopian traditional musical instruments, namely, washint, kerrar, and masinko and this has enabled me to put some of my poems to music and express how I feel deep inside. I am successful personally and professionally and I have reached the peak of my profession. But I never forget my roots and my humble background. The depth from which I have come and the heights to which I have climbed would not have been possible without God's blessings, people's generosities, and my own relentless quest for education and adventure. I am and will remain exceedingly grateful for all the blessings I have enjoyed in life. My philosophy in life is to reach out and help people in the same way that others reached out to me when I needed their help. With God's help, I will continue helping others in need as I have been helped when in need.

In 2009, something wonderful happened almost unexpectedly. It became possible for me to build a school in my old village to educate the grandchildren of my relatives and my childhood friends. What a life changing miracle! Over five decades ago, I left my beloved village and everyone I loved behind. And I did so in search of education. Today, there is a school in my village and there are five hundred students in that school already. No doubt the school will continue to grow. My lifelong dream has finally been fulfilled. Education will transform the lives of hundreds and thousands of rural boys and girls as it transformed mine. What a privilege! And what a wonderful feeling to think that I played a role in this monumental project in the middle of nowhere. Let me hasten to state that two wonderful foundations and many generous individuals made this dream come true. May they all be abundantly blessed!

Finally, let me say a word about my eye that catapulted me to a world of adventure, enlightenment, and a better way of life. I have had four surgeries and my vision has been partially restored. The first surgery removed the cataract caused by the accident. The second surgery corrected the stigmatism caused by the accident and the first surgery. An artificial lens was also implanted to replace my damaged natural lens. The third surgery replaced the first lens implant with a much improved lens and also transplanted a cornea. The fourth surgery cleaned up scar tissues and opened up the eye for more light exposure. My vision is still not perfect but the surgeries have been worth the pain and suffering. I must confess however that I have often wished I had better vision in my left eye. But I don’t want to complain, because my eye accident has been a tremendous blessing in disguise.

I believe that my experience is a case in point that tragedies and bad experiences can often become opportunities if one manages to look beyond them. While it is true that bad things happen to good people, it is also true that good things can come out of bad situations, if one keeps trying to overcome challenges. To anyone experiencing challenges and difficulties in life, I say don't give up! To any one who can make a difference in someone else’s life, I say it is worth it! To anyone who is cynical about people, I say there are wonderful people everywhere. To anyone who says it is too late for me, I say it is never too late. To anyone who has given up on God, I say not so fast. He is the only one out there who can give courage and restore hope. He is personally interested in us and blesses our efforts. I have been a grateful recipient of God’s grace and people’s generosity and I now try my best to be a cheerful giver to those in need. I know by personal experience that “it is more blessed to give than to receive”. Try it and see!

My name is Adugnaw Worku and I was born and brought up in northwest Ethiopia. My parents were peasant farmers like everyone else in the area and I was destined to continue the family tradition as a country farmer. From age seven to twelve, I was a shepherd and my assignment was taking care of goats, sheep, and cattle. At age twelve, I handed over the shepherding assignment to my younger brother and moved on to the family farm. My father taught me what his father had taught him about farming. He taught me how to harness the oxen, how to plow in a straight line, how to sow the seeds, how to weed, and how to harvest. I worked side by side with my father and I was fully trained by age fifteen. Every year, we planted and harvested various crops we needed to live on. We had to buy salt, shirts and pants and some farm equipment in the open market and cash crops like oil seeds, cotton, and spice made it possible for us to do so.

My name is Adugnaw Worku and I was born and brought up in northwest Ethiopia. My parents were peasant farmers like everyone else in the area and I was destined to continue the family tradition as a country farmer. From age seven to twelve, I was a shepherd and my assignment was taking care of goats, sheep, and cattle. At age twelve, I handed over the shepherding assignment to my younger brother and moved on to the family farm. My father taught me what his father had taught him about farming. He taught me how to harness the oxen, how to plow in a straight line, how to sow the seeds, how to weed, and how to harvest. I worked side by side with my father and I was fully trained by age fifteen. Every year, we planted and harvested various crops we needed to live on. We had to buy salt, shirts and pants and some farm equipment in the open market and cash crops like oil seeds, cotton, and spice made it possible for us to do so.Work on the family farm was backbreaking and the farm equipment we used was primitive and ineffective. We depended completely on seasonal rhythms and weather patterns and hoped and prayed for rain constantly. There were no reservoirs to capture rainfall, and we did not use river dams for irrigation. Consequently, we had only one harvest a year and that did not give us adequate reserves for emergencies. One bad season with little or no rain often put us in precarious situations almost immediately.

In short, my recollections of life on the family farm are mixed at best. There were happy times to be sure. As long as we had adequate rain and a good harvest, we were able to enjoy weddings, holidays, and the many social and religious festivities with family and friends. But we lived a year at a time and almost always on the edge. We depended on God and on our own ingenuity to survive. I have absolutely no recollection that the government did anything for us by way of educating us to become better farmers, or helping us develop better farm tools. There was no health care of any kind and infectious diseases wreaked havoc in our lives. A lot of children died in those days. My poor parents lost seven children. The government did absolutely nothing to help us. What I remember is the additional burdens the government imposed on us every year. And what a burden that was! The tax collectors showed up right after harvest every year and demanded an arm and a leg. They were harsh and very callous.

In short, my recollections of life on the family farm are mixed at best. There were happy times to be sure. As long as we had adequate rain and a good harvest, we were able to enjoy weddings, holidays, and the many social and religious festivities with family and friends. But we lived a year at a time and almost always on the edge. We depended on God and on our own ingenuity to survive. I have absolutely no recollection that the government did anything for us by way of educating us to become better farmers, or helping us develop better farm tools. There was no health care of any kind and infectious diseases wreaked havoc in our lives. A lot of children died in those days. My poor parents lost seven children. The government did absolutely nothing to help us. What I remember is the additional burdens the government imposed on us every year. And what a burden that was! The tax collectors showed up right after harvest every year and demanded an arm and a leg. They were harsh and very callous.My parents were very intelligent and proud Ethiopians. My father fought against the Italian occupiers for five years and he voluntarily served as a community leader during most of his adult life. Unfortunately, my parents were illiterate. They had no opportunity to learn to read and write, or even sign their names. Religious education existed in Ethiopia for hundreds of years but it was limited to those chosen to serve the church and the government. As a child, I was very curious and enjoyed learning new things. I recognized the value of education instinctively and begged my father to allow me to attend the local priest school. Some of my childhood friends were attending priest schools and they were able to read, sing, and serve in the local churches. But my father told me in no uncertain terms that being a farmer was better than being a priest. His best wishes and desires for me were to be a good and successful farmer, get married, raise a family, and continue the family tradition of farming. I was not satisfied or pleased with my father's vision for my life and I took matters into my own hands when I was about nine years old. I left home without my father's permission and enrolled myself in a priest school far from home, so I thought. I was enjoying school and I was learning a lot. But one day, my father showed up from nowhere and told me to pick up my belongings and go home. I returned home broken-hearted and very unhappy. Fortunately, that was not the end of the story because better educational opportunities came later and unexpectedly.

When I was fifteen years old, an unexpected event drastically changed the course of life. I had a freak accident which left me blind in the left eye. My lens was destroyed and my cornea was scratched. In addition, I developed a traumatic cataract on that same eye with a white patch covering the middle of it. Both the loss of vision and the disfigurement were hard to take for me personally and for the family as a whole. The best medicine men and women in my village and in the surrounding area tried to help me. But the accident was too severe to respond to traditional herbal medication. In desperation, my family decided to send me to a modern hospital for treatment. I walked with a group of merchants for two days to reach a city called Debretabor. This was the first time I was away from home and the farthest I had ever travelled. I was full of anxiety, expectation, and hope. I had not been to a big city before and Debretabor appeared to me to be a big city. Some of my mother's relatives lived in Debretabor and finding out where they lived was my first a challenge. In the countryside, everybody knew where everybody else lived but it was not so in the big city.

The hospital at Debretabor was a Seventh-day Adventist hospital and the physician at the time was a missionary doctor from Norway by the name of Dr. Christian Hogganvik. Dr. Hogganvik looked at my eye and shook his head. Then he informed me through a translator that he was not an eye doctor and that I had to go either to Asmera or Addis Ababa. Once again, I was very disappointed. But something wonderful and profoundly life-changing happened to me while I was in Debretabor. I observed boys and girls going to school every day. And they were able to read and write. Here I was more than twice their age at fifteen years of age unable to even sign my name. Once more, I took matters into my own hands and did not seek my father's permission. I decided to go to school by whatever means I could possibly find. I had only two Ethiopian Birr in my pocket and I had nothing more than the clothes on my back. But my desire for education was intense and I was prepared to do anything. What I did next amazes even me in hind sight.

I literally went from door to door and asked people to give me food and shelter in exchange for work after school. In those days, school was only in the morning and the whole afternoon was available to work on the farm or in the garden. When I asked for food and shelter in exchange for work after school, some people laughed at me. Others admired my determination and felt sorry for me for attempting the impossible. But with luck, determination, and providential help, I became a proud first grade student at the age of fifteen and half, and I never looked back. I found school much easier than farm work and thoroughly enjoyed the enlightenment and the pleasure it brought to my life. By the time I reached grade eight, I had lived with five different families who treated me with love, kindness, and generosity. In my spare time, I cut grass and gathered and carried fire

wood from the forest and sold them to earn money for clothes and school supplies. I am eternally grateful to those generous Ethiopian families that came to my rescue during those critical early years of my education and for treating me as if I was their son.

When I was in grade eight, an American missionary family from the United States came to Debretabor and one of the family members by the name of Carolyn Stuyvesant became my teacher. I got to know this wonderful missionary family well and eventually asked them if they could help one of my brothers to come to school. To my pleasant surprise, they agreed. In exchange, I worked for them. A year later, this wonderful missionary family volunteered to help my other brother and my sister who were still at home. Today, all four of us are college educated.

I owe Dr. Harvey Heidinger, his wife, Elizabeth, and her sister Carolyn Stuyvesant a debt of gratitude more than words can ever express. These people of God changed our lives dramatically. Who would have thought that four peasant children from the same family would attend school and eventually graduate with university degrees? I started school very late, but I got it done eventually. I graduated from grade eight at age twenty two and from high school at twenty six. Then, I got an opportunity to go to Australia for my college education and graduated there at age thirty. Today, I hold three graduate degrees and an honorary doctorate. What a difference education makes! I thank God and people of good will for giving me the best gift in life, which is the gift of education.

My regret in life has been that I have not returned home to Ethiopia to help my country and my

people with the education and experience I have gained. I have been around the world; I have written two books and numerous articles, and I have produced CDs and DVDs of music and poetry. I have been fortunate and enormously blessed. But the boys and girls I grew up with in my village and in the surrounding villages have not been so fortunate. They never got the opportunity to realize their potential. I find that profoundly sad. I think of them often and wish that they had the same opportunity I have had. I can only imagine what they would have become if they were educated. To this day, their potential remains shrouded in a dense fog of ignorance, superstition, and grinding poverty. Life is very difficult for them and they struggle daily to make ends meet. To think that I can make more money in a few days than they can in a whole year is simply astounding. Education made that possible for me.

|

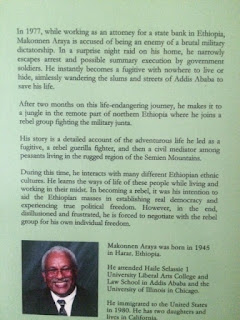

| Adu and Zewditu |

I dream day and night about Ethiopia and my people and I talk, write, and sing about them. Most of my professional and recreational writing and music has to do with homeland. As mentioned earlier, I have written two books and numerous articles. I have produced cassette tapes, CDs and DVDs and they are all about home sweet home. I play three Ethiopian traditional musical instruments, namely, washint, kerrar, and masinko and this has enabled me to put some of my poems to music and express how I feel deep inside. I am successful personally and professionally and I have reached the peak of my profession. But I never forget my roots and my humble background. The depth from which I have come and the heights to which I have climbed would not have been possible without God's blessings, people's generosities, and my own relentless quest for education and adventure. I am and will remain exceedingly grateful for all the blessings I have enjoyed in life. My philosophy in life is to reach out and help people in the same way that others reached out to me when I needed their help. With God's help, I will continue helping others in need as I have been helped when in need.

I dream day and night about Ethiopia and my people and I talk, write, and sing about them. Most of my professional and recreational writing and music has to do with homeland. As mentioned earlier, I have written two books and numerous articles. I have produced cassette tapes, CDs and DVDs and they are all about home sweet home. I play three Ethiopian traditional musical instruments, namely, washint, kerrar, and masinko and this has enabled me to put some of my poems to music and express how I feel deep inside. I am successful personally and professionally and I have reached the peak of my profession. But I never forget my roots and my humble background. The depth from which I have come and the heights to which I have climbed would not have been possible without God's blessings, people's generosities, and my own relentless quest for education and adventure. I am and will remain exceedingly grateful for all the blessings I have enjoyed in life. My philosophy in life is to reach out and help people in the same way that others reached out to me when I needed their help. With God's help, I will continue helping others in need as I have been helped when in need.In 2009, something wonderful happened almost unexpectedly. It became possible for me to build a school in my old village to educate the grandchildren of my relatives and my childhood friends. What a life changing miracle! Over five decades ago, I left my beloved village and everyone I loved behind. And I did so in search of education. Today, there is a school in my village and there are five hundred students in that school already. No doubt the school will continue to grow. My lifelong dream has finally been fulfilled. Education will transform the lives of hundreds and thousands of rural boys and girls as it transformed mine. What a privilege! And what a wonderful feeling to think that I played a role in this monumental project in the middle of nowhere. Let me hasten to state that two wonderful foundations and many generous individuals made this dream come true. May they all be abundantly blessed!

Finally, let me say a word about my eye that catapulted me to a world of adventure, enlightenment, and a better way of life. I have had four surgeries and my vision has been partially restored. The first surgery removed the cataract caused by the accident. The second surgery corrected the stigmatism caused by the accident and the first surgery. An artificial lens was also implanted to replace my damaged natural lens. The third surgery replaced the first lens implant with a much improved lens and also transplanted a cornea. The fourth surgery cleaned up scar tissues and opened up the eye for more light exposure. My vision is still not perfect but the surgeries have been worth the pain and suffering. I must confess however that I have often wished I had better vision in my left eye. But I don’t want to complain, because my eye accident has been a tremendous blessing in disguise.

I believe that my experience is a case in point that tragedies and bad experiences can often become opportunities if one manages to look beyond them. While it is true that bad things happen to good people, it is also true that good things can come out of bad situations, if one keeps trying to overcome challenges. To anyone experiencing challenges and difficulties in life, I say don't give up! To any one who can make a difference in someone else’s life, I say it is worth it! To anyone who is cynical about people, I say there are wonderful people everywhere. To anyone who says it is too late for me, I say it is never too late. To anyone who has given up on God, I say not so fast. He is the only one out there who can give courage and restore hope. He is personally interested in us and blesses our efforts. I have been a grateful recipient of God’s grace and people’s generosity and I now try my best to be a cheerful giver to those in need. I know by personal experience that “it is more blessed to give than to receive”. Try it and see!